I recently completed a second AmeriCorps term with the National Park Service, working in the Ocean and Coastal Resources branch. My task was to research ballast water transport of invasive species and report on ways the parks might respond to the issue.

Humans transport organisms all over the world in a variety of ways, from muddy boots to bugs tucked in produce shipments. One prolific vector is ballast water: water that vessels – often very large cargo ships – use to maintain buoyancy in different voyage and cargo conditions. Vessels typically uptake ballast water straight from the ocean and all the little aquatic organisms in it come along for the ride. This includes critters ranging from human pathogens like E. coli to microscopic crab larvae. Ballast water has introduced some very high-profile invasive species to new locales, such as the zebra mussel to the Great Lakes.

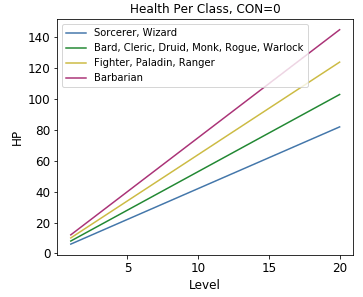

Luckily, we’ve developed multiple treatment strategies for reducing the organism load in ballast water, and increasing levels of regulation mean that invasive species transport will continue to decrease over time. (Of course, it’s another one of those environmental issues where you think “if only we started this fifty years ago instead of twenty…”, but I try not to dwell on that too much.)

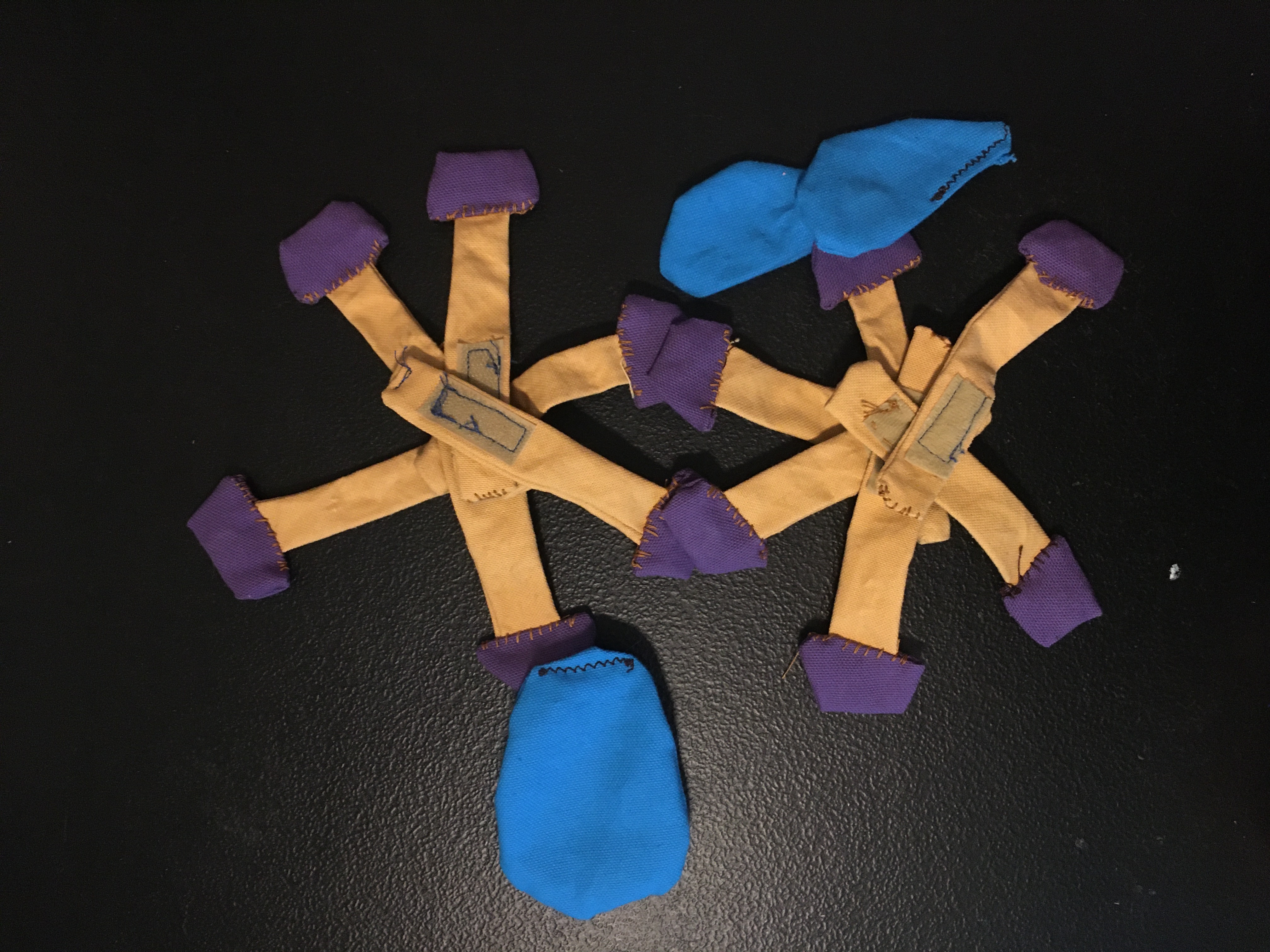

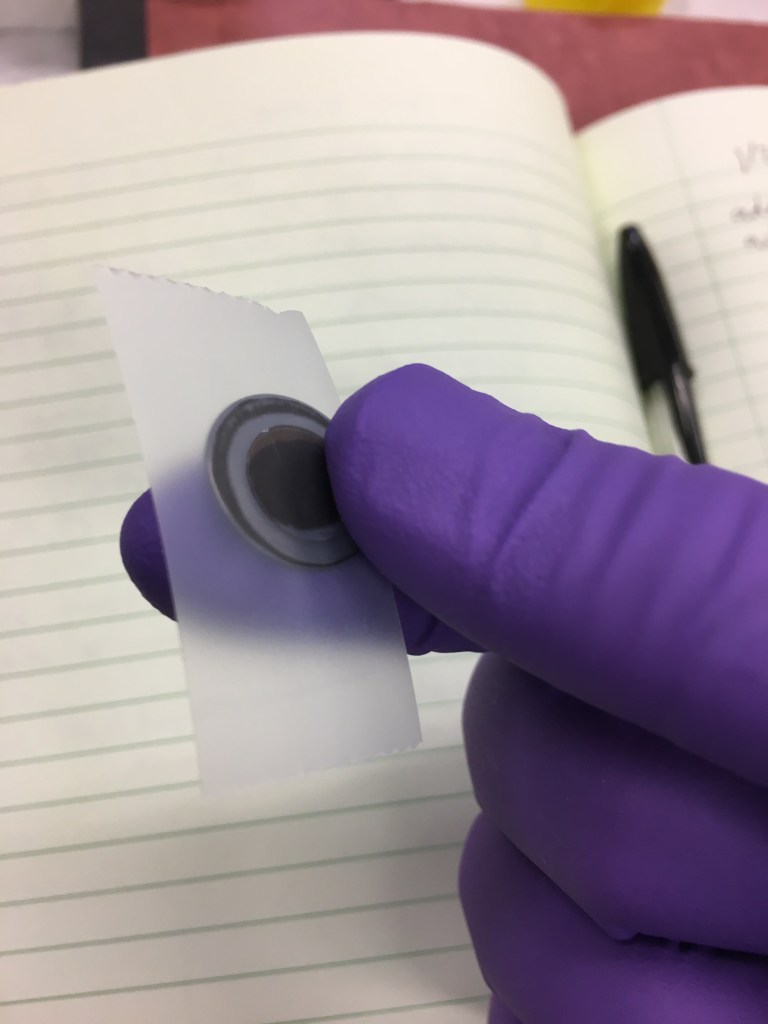

For the outreach component of my internship, I developed a hands-on activity demonstrating how human activity moves organisms around the world. The activity is simple: a guest pushes a magnetic model boat across the ocean, and it picks up magnetic organisms. When the boat reaches the opposite shore, stronger magnets pull the “organisms” off the boat, representing the introduction of a species to a new location.

Finally, in order to demonstrate that it is possible to prevent species introduction, I included a purple magnetic wand to represent the use of ultraviolet light to disinfect ballast water.

I made three of these activities (in-progress shots below) and they’ve been shipped out for use at Isle Royale National Park and Indiana Dunes National Park. Maybe someday you’ll encounter them out there!